NOW is the time to break barriers for women in aviation.

I shared this call to action with lawmakers earlier this month when I testified before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) — a body I’m proud to have served for nearly 15 years in my pre-NTSB days.

It was the T&I Committee’s first hearing as it prepares to work on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) reauthorization bill. In the words of Chairman Sam Graves, the bill is an unmissable opportunity to enhance “America’s gold standard in aviation safety.”

Make no mistake: the lack of diversity in U.S. aviation is a safety issue, which is why I’m so glad Congressman Rudy Yakym asked me about it.

The State of Women in Aviation

I’m only the fourth woman to serve as NTSB Chair since the agency was established in 1967 — 55 years ago.

Unfortunately, my story isn’t unique; women are underrepresented across transportation in every mode and nearly every job category, especially in roles that tend to pay more, such as upper management and highly technical positions.

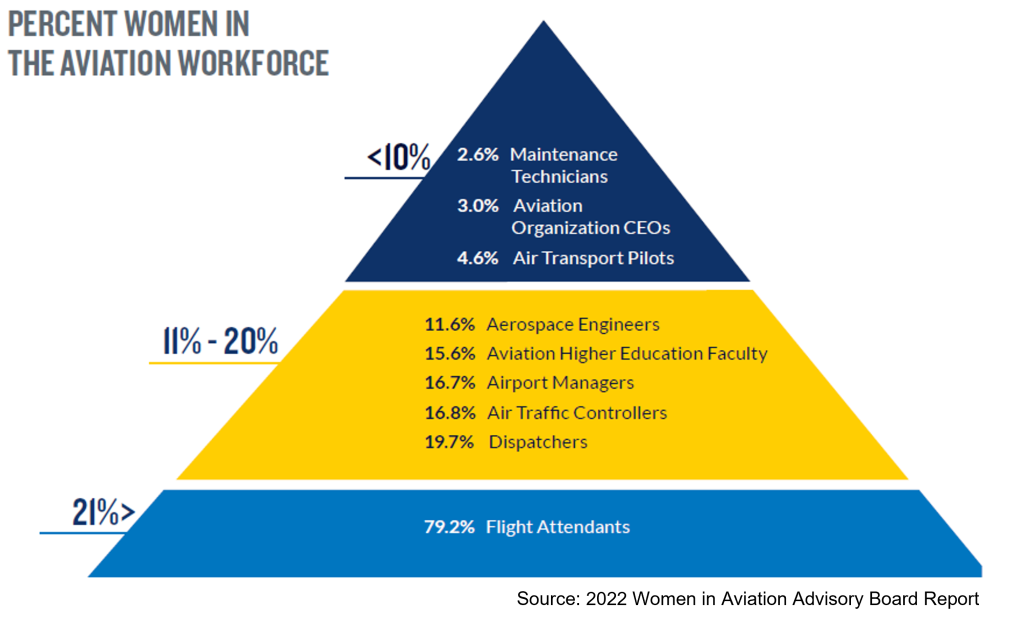

Aviation is no exception, where the data are startling: women hold less than 8% of FAA-issued pilot certificates.

Things are improving, but not fast enough. In fact, the share of commercial pilot certificates held by women is increasing at a rate of approximately 1% a DECADE. That’s unacceptably slow progress.

There’s also an unacceptable lack of ethnic and racial diversity among U.S. pilots, 94% of whom are white…and less than 0.5% of whom are Black women.

Other roles in aviation show a similar trend when it comes to gender diversity. Women represent 19.7% of dispatchers, 16.8% of air traffic controllers, 3% of aviation CEOs, and less than 3% of maintenance technicians. I could go on.

The System-Level Change We Need

What’s keeping women out of the control towers, off the tarmac, and everywhere in between — and what can we do about it?

The Women in Aviation Advisory Board (WIAAB) set out to answer these questions. Convened by Congress, the board’s charge was to develop recommendations and strategies to support female students and aviators to pursue a career in aviation.

The board concluded its work last year with a groundbreaking report, whose findings are best understood with an example.

Let’s use a hypothetical young woman who dreams of flying when she grows up.

I’ll call her “Lexi.”

Barriers to Entry

Lexi will face significant barriers to entering aviation at all stages of her life — and they present sooner than you might think.

As one survey revealed, more than half (54%) of women in aviation cited childhood exposure to the field as a positive influence on their decision to pursue an aviation career.

Conversely, 70% of women outside the industry say they never considered aviation. The most common reason they cited? A lack of familiarity with aviation-related opportunities.

In other words, exposing young kids to aviation is a powerful step we can take toward our diversity goals.

That means Lexi is more likely to become a pilot if someone exposes her to it before she’s 10 years old.

As Lexi grows up, society will send her powerful messages about who “belongs” in aviation. The WIAAB report points out, “During the secondary school years (ages 11–18), girls continue to be subjected to gender-limiting stereotypes and face bias and harassment for behaving outside of societal norms.”

Without intervention, repeated exposure to such negative messages can end Lexi’s aviation career before it even begins.

Barriers to Retention

Getting more women to enter aviation is only half the battle; we need to ensure they stay once they get there. Let’s assume Lexi is one of them.

Lexi is now a young adult. She’s completed her studies, graduated at the top of her class, and earned her pilot’s certificate. She’s thrilled to accept an offer to work as a commercial pilot.

At her new job, Lexi quickly makes a group of friends: 9 other women in aviation who defied the odds to be there. They “made it.”

The heartbreaking truth is that 6 of those 10 women will consider leaving aviation before long. Chances are, it’ll include Lexi.

What could possibly force Lexi and five of her colleagues from a job they’ve each dreamed about since childhood…one they worked incredibly hard to get?

In short: implicit bias discrimination, lack of career opportunities, and lack of flexibility and work-life balance. That’s what the WIAAB report shows.

The report also reveals chilling statistics on the prevalence of sexual harassment. Among women in aviation:

- 71% report experiencing sexual harassment at work or in an aviation setting.

- 68% of flight attendants experienced sexual harassment during their flying career.

- 51% who reported or complained about sexual harassment experienced retaliation.

- 62% say sexual harassment remains a significant problem in the aviation industry.

- 81% say they’ve witnessed sexual harassment in the workplace.

It’s not right and it’s not safe — for anyone.

The Safety Implications

Keep these statics in mind. Now, consider this line from NASA’s Safety Culture Model, which was developed following the 1986 Challenger disaster: “No one should ever be afraid to speak up; it could save a life.”

How could a woman like Lexi feel safe speaking up if she’s being harassed at work? And retaliated against for reporting it?

It’s clear that our aviation safety culture is falling short on NASA’s measure.

The Royal Aeronautical Society makes the case succinctly: “Without an inclusive environment, there can be no guarantee of safety.”

Fortunately, the opposite is also true: an inclusive culture can make everyone safer.

That’s why the WIABB recommends interventions like creating an industry-wide reporting system on gender bias. Imagine for just a moment what that could do to attract women to careers in aviation and ensure they stay. It’d be game-changing.

Now imagine ALL 55 of the WIAAB recommendations are implemented — it would transform aviation.

THAT’s how we create a more inclusive aviation culture, one that attracts and retains people from all walks of life…one that makes our skies safer for everyone.

We also need to give credit where it’s due. Many in the aviation industry are taking proactive steps that are also having a tremendous positive effect. For example, several commercial airlines have launched pilot training academies to diversify their applicant pool, efforts that I applaud!

The next step, as I see it, would be for the entire industry and labor to combine efforts. Such an action could supercharge progress toward our diversity goals. It would also allow industry and labor to defray the costs associated with investing in tomorrow’s aviation workforce…an investment from which we all benefit.

A Personal Take

I want a different future for women in aviation. Women like Lexi…whose aviation career, I’ll now admit, isn’t hypothetical.

Lexi is my daughter.

Though she’s now 15 years old, Lexi has known for years that she wants to be an aerospace engineer when she grows up. She even spoke about her passion for flying at last year’s Women in Aviation International Conference. I’m incredibly proud of her.

I have no doubt that my daughter will make her aviation dreams come true. And yet, I worry about the culture she’ll encounter once she gets there, and not just because I’m her mom — but because a more inclusive aviation culture will make everyone safer. I also think about the other little girls who never know that aviation is a viable dream in the first place.

Luckily, the Women in Aviation Advisory Board has provided us with a “flight plan for the future,” which gets at the root causes of our diversity problem.

Let’s get to work. Our “gold standard” of aviation safety depends on it.